Education is the key to success, at least that’s what everybody is told from an early age. It is no wonder then that today’s college degree is the previous generation’s high school diploma. Everybody wants in on the action. However, with this influx of college graduates flooding the market and a beat up economy with limited employment opportunities in place, more and more college graduates opt for even more schooling by enrolling in graduate school. With a deadly combination of lay prestige and attendance requirements bordering on open enrollment, one of the most appealing options is law school. There is one problem: law school isn’t cheap. In major cities, the cost of attendance over the 3 years often totals over $200,000 at sticker price. Even relatively cheap state law schools often hit the six-figure mark when all is said and done. This type of price tag ensures most law students will be financing their law school education with government student loans. But financing any type of education with student loans adds a financially significant wrinkle to the equation. Much to the disappointment of many prospective law students, student loan money is in fact real money. Non-dischargeable in bankruptcy barring extremely dire circumstances, this money will follow a student until it is paid off or at best forgiven decades in the future. Unfortunately, very few prospective law students consider these financial implications prior to the arrival of that first monthly student loan payment six months after graduation. With the legal market constricting, it is imperative anybody thinking about financing law school with student loans understands some very important factors before signing on the dotted line and sending over that student loan disbursement to any given law school.

Education is the key to success, at least that’s what everybody is told from an early age. It is no wonder then that today’s college degree is the previous generation’s high school diploma. Everybody wants in on the action. However, with this influx of college graduates flooding the market and a beat up economy with limited employment opportunities in place, more and more college graduates opt for even more schooling by enrolling in graduate school. With a deadly combination of lay prestige and attendance requirements bordering on open enrollment, one of the most appealing options is law school. There is one problem: law school isn’t cheap. In major cities, the cost of attendance over the 3 years often totals over $200,000 at sticker price. Even relatively cheap state law schools often hit the six-figure mark when all is said and done. This type of price tag ensures most law students will be financing their law school education with government student loans. But financing any type of education with student loans adds a financially significant wrinkle to the equation. Much to the disappointment of many prospective law students, student loan money is in fact real money. Non-dischargeable in bankruptcy barring extremely dire circumstances, this money will follow a student until it is paid off or at best forgiven decades in the future. Unfortunately, very few prospective law students consider these financial implications prior to the arrival of that first monthly student loan payment six months after graduation. With the legal market constricting, it is imperative anybody thinking about financing law school with student loans understands some very important factors before signing on the dotted line and sending over that student loan disbursement to any given law school.

Student Loans and Your Financial Future

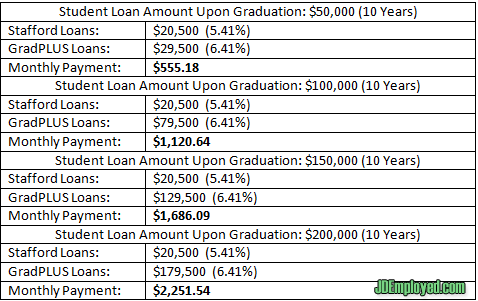

When used within reason, federal student loans can serve as an important backbone of financing your education. However, with egregious interest rates accumulating on top of the initial principal in rapid fashion, there’s not much room before a student’s educational debt load starts becoming unmanageable. The extent of this problem is often only understood from personal experience, but some basic examples may help illustrate the point ahead of time. The following examples define the student loan amount upon graduation and use the 10-year standard repayment plan, which means the expected monthly payments after graduation will need to be paid for 10 years before the student debt is repaid. In addition, it is assumed that the initial $20,500 of the loan amount belongs to Stafford loans and the remaining loan amount is composed of GradPLUS loans (for calculating interest rates).

The above chart assumes that the current student loan interest rates on Stafford loans and GradPLUS loans remain constant, an unlikely scenario after July 2013 when these interest rates became variable. Considering the economy had not recovered as of mid-2013, these initial interest rates represent a low point and are expected to rise over the years. This, of course, means that these expected monthly payments may very well be a bit bigger depending on the year of any particular loan’s disbursement.

There are two major takeaways from this chart. First, even a student taking out a meager $50,000 to help finance law school, a low figure considering the average private law school student’s debt is $125,000, must pay over $500 each month just to get rid of that student debt within 10 years. Over $500 every single month, for 10 years. That’s almost a rent figure in some parts of the country. The higher debt totals and their accompanying monthly payments speak for themselves. Second, the fact a student with only $50,000 in student debt upon graduation must pay over $500 every single month cannot be seen in a vacuum. That $500 student debt payment is but a piece of the graduate’s entire financial exposure each month. In other words, without accounting for any other expenses such as food, a cell phone, internet, clothes, and anything you can imagine, over $500 must be forked over automatically each month without second thought if the student wishes to avoid default and be done with the repayment within 10 years. This drives another point home: this pretty high amount is only high enough to allow the graduate off the hook after 10 years. For a K-JD student with no work experience between college and law school, that means student debt freedom in the mid-30s. In the mean time, outside of the regular expenditures mentioned above, what about any savings, retirement, and perhaps even home ownership funds?

It’s Not Just About Jobs, But Good Jobs

When student loan payments are an additional payment that needs to be accounted for each month, even excluding the most basic and essential financial expenditures, a graduate must possess a job after graduation that is able to service that monthly payment if he or she wishes to be up to speed on servicing that loan. But only a little more than half of law graduates are able to find legal employment after graduation. The rest are unemployed or underemployed. Even if some have the ability to stay with their parents, who can provide a financial safety net that covers basic necessities, that student loan payment still needs to be paid to avoid default and to ensure freedom in as fast as 10 years. Otherwise, the longer that principal remains unpaid, the longer that monthly payment will need to be made. Being underemployed or unemployed certainly doesn’t help this. However, even being on the right side of the fence by obtaining legal employment after graduation doesn’t end the inquiry. When student loans are at play it is no longer reasonable to dive head first into a graduate program like law school without understanding not only the probability of obtaining legal employment after graduation but legal employment that can service the graduate’s student loan payments as well. Any legal job with any salary isn’t sufficient, a good job is required. A good job refers to a job with a salary capable of servicing both the student debt payments and the basic necessities required to avoid living in your parents’ basement.

The problem with the legal field is that legal salaries are sharply divided into two prongs: the high-cash big law firm salaries reserved for the top few percent of graduates, and the mediocre to downright depressing salaries of the vast majority of the remaining legal positions. This is known as bimodal distribution. There are two high peaks, with not much in between. It just so happens that the high-salary peak is very narrow, and the low-salary peak is very wide. Therefore, even for the law graduates who wind up obtaining legal employment, this is what often crushes their reality if they do not achieve the big law position or luck into a very limited but equally competitive amount of public legal positions that qualify for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). Because almost all prospective law students decide to enroll in law school to enhance their lot in life, hoping the JD degree will provide job security, career growth, and financial independence, how awful must it be when many take out over $50,000 to finance their law school education only to wind up unemployed, underemployed, or in a legal position with a starting salary of 30-50K? In what way has the law degree enhanced their lot in life? The greatest salt on their wound is that the 30-40-50K salary job could have been obtained elsewhere without enrolling in law school, and more importantly, taking out that student debt.

With this in mind, any prospective law student wishing to go to law school backed by student loans must understand the statistical unlikelihood of landing a big law position or a public legal position that qualifies for PSLF. To the extent any legal employment will be obtained, it will very likely start out at an unexpectedly low salary. In addition, although there is always room for growth with experience, it’d be foolish to believe starting out a small firm initially will pave the way for a lateral to a big law firm and a much bigger salary later on down the line. This is just unlikely. Because of all of this, if law school is on a student’s radar, everything possible must be done to limit the potential student debt load upon graduation. This will allow the student much more flexibility if things don’t pan out as expected. Unable to predict what may happen, the least a prospective law student should do is limit his or her student debt load upon graduation through scholarships, part-time jobs, delaying law school and working to save up, and any other method.

IBR/PAYE Is a Crutch, Not An Acceptable Lifestyle

Enrolling into IBR or PAYE after graduation are methods of getting by if a good legal job upon graduation is not obtained. Although these student loan repayment plans are fantastic options, they were never meant to be advertised as viable options for the masses. These programs were merely a response to the growing concern that some college or graduate program graduates cannot make financial ends meet because of high monthly student loan payments and a lack of good jobs after graduation. Regarded as short-term solutions, they were meant to be used as nothing more than a crutch that allows graduates in temporarily dire financial circumstances to get by until good jobs are obtained. In this moment of temporary delay, these programs are a great financial safety net. To account for a rare worst case scenario, a final “saving grace” was added that allows a graduate’s debt to be forgiven over the course of 20-25 years in exchange for paying the debt forgiveness tax (currently 33% of the total loan amount upon forgiveness). But this isn’t exactly a saving grace considering the graduates most likely to wind up dealing with this tax down the line are graduates whose debt spiraled so out of control they were never able to get back on track. With these egregious interest rates in place, after 20-25 years that tax may very well wind up being as high or even higher than the graduate’s initial debt load upon graduation. It’s a lose-lose situation.

The big problem with these plans is that no one enrolling in law school voluntarily wants to be on them after graduation. Having to go on IBR or PAYE is not a victory dance, it’s a sign of financial trouble. It is not far-fetched to assume that nobody knowingly signs up for an extra 3 years of higher education after college only to wind up in a position where he or she is unable to service his or her student loan amount on a 10-year plan. Unless law school is an extended 3 year vacation, having to enroll in IBR or PAYE is a sign that law school, at least temporarily, has been a financial disappointment. Of course, because these generous repayment options exist, there’s nothing wrong with signing up for them to start the forgiveness meter running even if much higher monthly payments are made, but law graduates in these positions are the exception, not the rule. For the vast majority that financed law school with student loans, having to enroll in IBR or PAYE is like waiving the white flag. One can hope many of these graduates find a good job, legal or not, that will allow them to get their loan payments back on track, but this is not very easy considering there’s a limited amount of legal jobs and the JD degree is not as versatile as some imagine. In addition, time is always ticking and setting back the goal posts as the interest on these student loans accrues. This is not an enviable position after 7 years of higher education. Even worse, with a little bit of research you can find plenty of law graduates on IBR or PAYE that are so far behind on their large student loan payments they are already thinking about preparing for the debt forgiveness tax 20-25 years from now. This means they fully understand that short of winning the lottery, their financial situation will never become good enough to clear those student loans. No matter your goals, law school should never lead to this result. To avoid this type of law school backfire or any situation you would not expect after graduating from law school, do your research and understand the financial risks law school presents.

JDEmployed Where Law School Meets the Legal Market

JDEmployed Where Law School Meets the Legal Market